台灣南方 當代原民藝術

Pingtung Sandimen Field Trip – Performing Arts in Local and International Contexts class

Pingtung (屏東縣) is the southernmost county in Taiwan, known for its warmer climate and for being home to the Sandimen Township, a mountain-based indigenous community composed mostly of Paiwan and Rukai people. The Sandimen region is part of the Wutai Township, which was among the ones that most suffered under the impact of the Typhoon Morakot a decade ago, in the early weeks of August 2009.

Much of the current cultural production of the Paiwan and Rukai peoples has been developed as a consequence of Morakot’s flooding and mudslides, which were responsible for the death of 681 people and for the displacement of many others. Morakot had especially harsh effects on those slope area communities.

It has been ten years since the incident, and part of these communities has been resettled in newly built homes within safe areas in Pingtung. Some of the Paiwan and Rukai people are even back to their former hometowns on the slopes, but the cultural effects of the devastation are very much present in the current homes and art production of these communities. IMCCI students could experience these effects first-hand during this weekend-long field trip.

The trip was part of the “Performing Arts in Local and International Contexts” class taught by professor I-Wen Chang and was designed for students enrolled in her class. It also welcomed interested second-year IMCCI alumni as well as postgraduate students from the Dance department. The goal was to immerse students in the most recent production of visual artists and contemporary dancers of Paiwan and Rukai background or inspired by those people’s cultures.

Photos by Larissa Soto Hermández

An early train ride took students from Taipei to Pingtung on Saturday morning, and after a little more than three hours of getting acquainted with the changing landscapes of the west coast of Taiwan, students arrived on a bright sunny late morning to the Pingtung Railway Station. The main area of the station introduced the IMCCI’s to an informal preview of the exhibition to come with a large-scale sculpture by Paiwan artist Sakuliu Pavavalung (撒古流 巴瓦瓦隆), one of the most distinguished contemporary artists of indigenous background in Taiwan. Sakuliu was the first artist of aboriginal background to be awarded the National Award for Arts in fine arts, in 2018.

Students were welcomed by a pair of local guides, also from an indigenous background, who took the group on a shuttle to a very symbolic place in Pingtung: the Taiwan Indigenous Culture Park, an 83-acre area dedicated to the preservation and diffusion of Taiwanese aboriginal cultures. With concert halls and theaters, multimedia rooms, exhibition halls, a library with research areas, traditionally built houses and a scenic glass bridge over the Ailiao River, the park offers many opportunities to experience local nature and cultural production.

The weekend field trip happened, coincidentally, on the International Museum Day, and the Indigenous Culture Park was celebrating the day with the opening of a contemporary indigenous art exhibition. The exhibition occupied the octagonal exhibition room as well as a great number of residences built in the traditional style of the local tribes, which served as pavilions for the artists’ works.

“When Kacalisian culture meets the vertical city — contemporary art from greater Sandimen” (當斜坡文化遇到垂直城市—大山地門當代藝術展) was curated by TNUA professor Manray Hsu (徐文瑞) and included 17 artists of different generations, artistic styles, and backgrounds. Besides curating this exhibition, professor Hsu teaches in art academies in Taiwan and abroad, has been the co-founder and director of Taipei Contemporary Art Center, has curated exhibitions including the Taipei Biennial, and has served as a juror for Venice Biennale and the Istanbul Biennial in 2001, among other committees.

Photo by 斜坡上的話-2019大山地門當代藝術節 Facebook

Curator and artists were joined by other known professionals in the field on a showcase of a local band, that, much in the spirit of the exhibition, combines indigenous and modern influences. The performers combined electrical guitars, bass, and indigenous drums, offering a mixture of rock, and indigenous rhythms. After the performance, the visual artists were introduced to the audience and lead the way to the exhibition areas, where each of them presented and commented on their works, inspirations and methods.

Students in the “Performing Arts in Local and International Contexts” class had the chance to get acquainted with some of these artists’ work at the exhibition “Malang – Aboriginal Contemporary Art Exhibition” (https://malang.cksmh.gov.tw/home) at the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, which included artists of Atayal, Seediq, Punuyumayan, Bunun and Payuan tribes’ background.

Some of these artists also featured at the Taiwan Indigenous Culture Park exhibition. Sakuliu and Aluaiy Pulidan were also part of the selection for the “Micawor – 2018 Pulima Art Festival” (http://www.mocataipei.org.tw/index.php/2012-01-12-03-36-46/current-exhibitions/2731-micawor-2018-pulima-micawor-2018-pulima-art-festival), presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei (MOCA) throughout 2018. The Pulima Art Festival (http://www.pulima.com.tw) is produced by the Indigenous Peoples Cultural Foundation (IPCF), which has the mission to “promote indigenous cultural education, and operate an indigenous cultural media” of 14 tribes in Taiwan, some of which were presented in these three exhibitions.

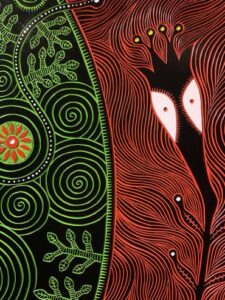

At the octagonal Exhibition hall, visitors were introduced to the artworks by Etan Pavavalung (伊誕 巴瓦瓦隆), whose carved lines and patterns reference natural elements of the Paiwan landscape. A few IMCCI students noted the similarities between Etan’s carvings and the printing techniques learned during the semester through their Fine Arts Seminar.

Aluaiy Pulidan (武玉玲) works occupied the entirety of the second floor and presented organic shapes that reference the impact of the destruction on her people’s slope lands, themes of life and death among women from her tribe, as well as site-specific work, created exclusively for the exhibition.

Kulele Ruladen (古勒勒.羅拉登) tells stories full of tribal symbology through colorful and sometimes violent illustrations. He is one of the most prolific artists in the exhibition, featuring a series of works in one of the exhibition halls, as well as one of the traditional Rukai stone hoses. His metal works draw from Rukai mythology symbols such as the serpent, the lily flower, and the eagle. The first series of work, hosted in the exhibition hall, share a theme of “cultural measurement devices”, which reference the not-so-methodical science and the prejudice that sustained of much of the colonial discourse on cultural hierarchies between civilized and ‘uncivilized’ peoples. His work at the Rukai ‘pavilion’ drew from very similar symbology and the same metalwork seen in the exhibition hall, although in smaller and more intimate compositions.

One of the slab houses displayed a working a fireplace that was lit during the opening, producing the same smoke that helped drive away insects and other threats on their original Rukai settings. The houses were made to let the smoke escape slowly, warming and protecting the internal environment and, at the same time, “breathing like its inhabitants”.

Sakuliu Pavavalung occupied a Rukai house neighboring Kulele Ruladen, with works that balanced delicate craftwork, very precise use of lighting and heavy socio-cultural criticism. A fragile image of a small child climbing a hanging ladder. A second child appeared to be collecting something from the grassy texture below while a third piece, a hanging chair appeared out of reach from both children. Sakuliu spent a great part of his presentation commenting on the economic, cultural and educational opportunities differences children from different backgrounds are exposed to and the social hierarchies that separate them from opportunities.

Photos by Clarissa Perrone Butelli & Larissa Soto Hermández

The artworks might seem to cover a wide range of themes and techniques, but, on a more attentive look, there are a few interesting underlying themes. The verticality of the sloped lands has its contrast in the verticality of the urban cities and how the cultural and economic relationship between these vertical – indigenous and urban – areas influence each new generation differently.

When curator Manray Hsu references a “new type of cosmology” in his statement, he gives an interesting title to a wide array of symbols and themes – traditional ones that have long been used by the tribespeople as well as very contemporary elements. It is a challenge, however, to draw quick conclusions from these productions, especially coming from urban backgrounds, as is the case with most IMCCI students. When observing a painting of a figure dressed in indigenous outfits and holding a colored tablet very similar to an iPad, students commented on the possible reference to an ‘invasion’ of technology to the local rituals. They were immediately corrected by the artists who mentioned that might be a common reading but the work simply reference the contemporary culture she and her tribespeople are immersed in.

After the tour and a final performance, students were welcomed to spend the night at the Evergreen Lily Elementary School. The school is also one of the consequences of Typhoon Morakot, although a positive one. It was founded by the local government, is financially supported by the Chang Yung-Fa Foundation and was built not only to host students of Paiwan and Rukai background, but also to provide ways in which they can effectively learn about their own culture. The school has a program specifically developed for local use: the Indigenous Cultural Curriculum.

On a short walk through the school installations, it is possible to spot and learn from a great variety of boards, games, educational tools and students’ own works. Information boards presenting local species of plants, game boards featuring Taiwan different indigenous peoples and their outfits, historical maps of Austronesian tribes and adapted Lego world maps with the maritime trajectories between the South Asian Pacific and the eastern edges of South America. A two-floor library, four pianos distributed through the corridors, a gym room with well-cared-for gymnastics equipment are some of the clues to the very healthy mixture of historical background and contemporary education the school provides to its students.

The next activity was a morning walk with the local guides, where IMCCI students learned a few other curiosities. The water lily used to represent the school and the local tribes, for instance, is also part of the decorative patterns local students produced for their ‘special events’ uniforms. This is an activity that is, at the same time, able to engage the students into working their artistic techniques and inspire pride for their own tribe’s symbology.

The walk led to a local artist’s workshop, where IMCCI’s were introduced to the symbology used in the painting outside of these constructions. The eagle that was very much present in artworks seen the day before gave way to the image of a goat facing the direction of the former habitat of the Sandimen peoples. It serves as a reminder that their original land is still calling for them, and as complete as the infrastructure of the current residences and installations seems to be, there is an underlying longing for the environment that had been part of their tribe’s history for generations, before the devastation of the typhoon came into play.

On a quick visit to the workshops’ souvenir store, IMCCI students were taught the close association between local crafts and elements of nature: how colors symbolize the water, the land and the other constant elements of the tribe’s daily lives. It was the last stop before heading back to the Taiwan Indigenous Culture Park, where a performance of symbolic rituals of many of the Taiwanese tribesmen and women was showcased. It was, perhaps, a more tourist-focused presentation of their dances. The arena-like stage was at the same level as the audience and the dark ambiance, with very few lights focused on the dancers, gave the performance theatrical overtones. Some of the most memorable examples were a ritual for the first immersion of a boat in the waters and the ‘waving hair’ dance performed by a group of women to wish for the seas to be gentle with their tribes’ fishermen. In the end, audience members were invited to perform a collective dance with their arms interlocked, surrounding the stage with a semi-circle of visitors of different ages and backgrounds.

The dance was an interesting preview to the workshop that followed in the afternoon – the Tjimur Dance Theater Company elaborates contemporary choreographies taking inspiration on dance movements, in some cases, very similar to the ‘human chain’ dance. Before students reached the dance studio, they walked through the Shanchuan Glass Bridge in a short warm-up for what would be an afternoon of very practical performance studies. Shanchuan is the longest suspension bridge in Taiwan, and it also is part of the recent, post-Morakot history of the region: it was built after a previous suspension bridge between Majia and Sandimen townships was torn by the typhoon.

The Tjimur Dance Theater Company already displays its uniqueness in the small posters distributed throughout the town on the way to the studio: the contemporary tailoring of the costumes used are combined with what seemed like very traditional indigenous outfit crafts. Instead of the highly colored and accessorized outfits students saw on the Culture Park performance, dancers displayed skirt-like, one-piece clothing in completely white or black colors. The excerpts from the performances on the screens at the entrance of the studio also showed highly athletic and strength-based movements that shared elements with the ones seen on the park performance earlier on.

Artistic Director Ljuzem Madiljin, and her sibling and choreographer Baru Madiljin presented the background of the company on a short talk as the introduction to the workshop. Through the afternoon, IMCCI students were joined by the company dancers in a series of what would look to the outsider as simple movements. The combination of precise breathing, posture and strength demands proved an interesting challenge, especially for students who, in their majority, come from backgrounds in which the body is not such a central tool.

After the introduction to the movements, the groups of students were, along with the dancers, invited to create and perform a short dance based on the series of movements learned. The four groups had a few minutes for creation, rehearsal, and presentation and the final result was critiqued by Ljuzem Madiljin, as a seamless transition to the final part of the workshop – a collective talk and final Q&A.

Photos by Larissa Soto Hermández

During this final process, students learned about the international presentations of the company, their creative and rehearsal process, the audition and selection process, the challenges with their growth as an organization and the attributions to each member as well as other interesting themes. The company’s website (https://www.tjimurdancetheatre.com/) features excerpts of their productions and might leave visitors wanting to attend the company’s performances. It is the same feeling IMCCI students felt after seeing a live excerpt from the company’s latest performance “Varhung: Heart to Heart”, showcased at the Brighton Festival a week after the workshop.

The workshop was a very fitting closure for the weekend-long field trip of a class which proposes to “offer insights into the social and political functions of dances in their historical and contemporary manifestations”.

Throughout the weekend, students were faced with contrasting and complementary definitions of what ‘indigeneity’, ‘contemporarity’, ‘tradition’ and ‘culture’ can be. One of the most striking points brought up in class, a week after the field trip, has to do with the expectations of what indigenous culture should be, especially from the perception of outside observers. There is the underlying belief that ‘preservation’ is a synonym to the maintenance of cultural elements in a static form, protecting these assets from further change. The discomfort a few students felt with the manner the artworks and the indigenous dance performance were presented is a very interesting indication of the expectations about what indigenous art and performance ‘should’ be.

In a certain way, Cultural Studies is an area in which students’ and researchers’ expectations must be constantly put in check, and these reactions are a positive effect of this process. On a class that focuses on performance, one of the most ephemeral forms of cultural production, the act of questioning and constructing new meanings for cultural ‘validity’ is a very healthy exercise.

– Written by Clarissa Perrone Butelli